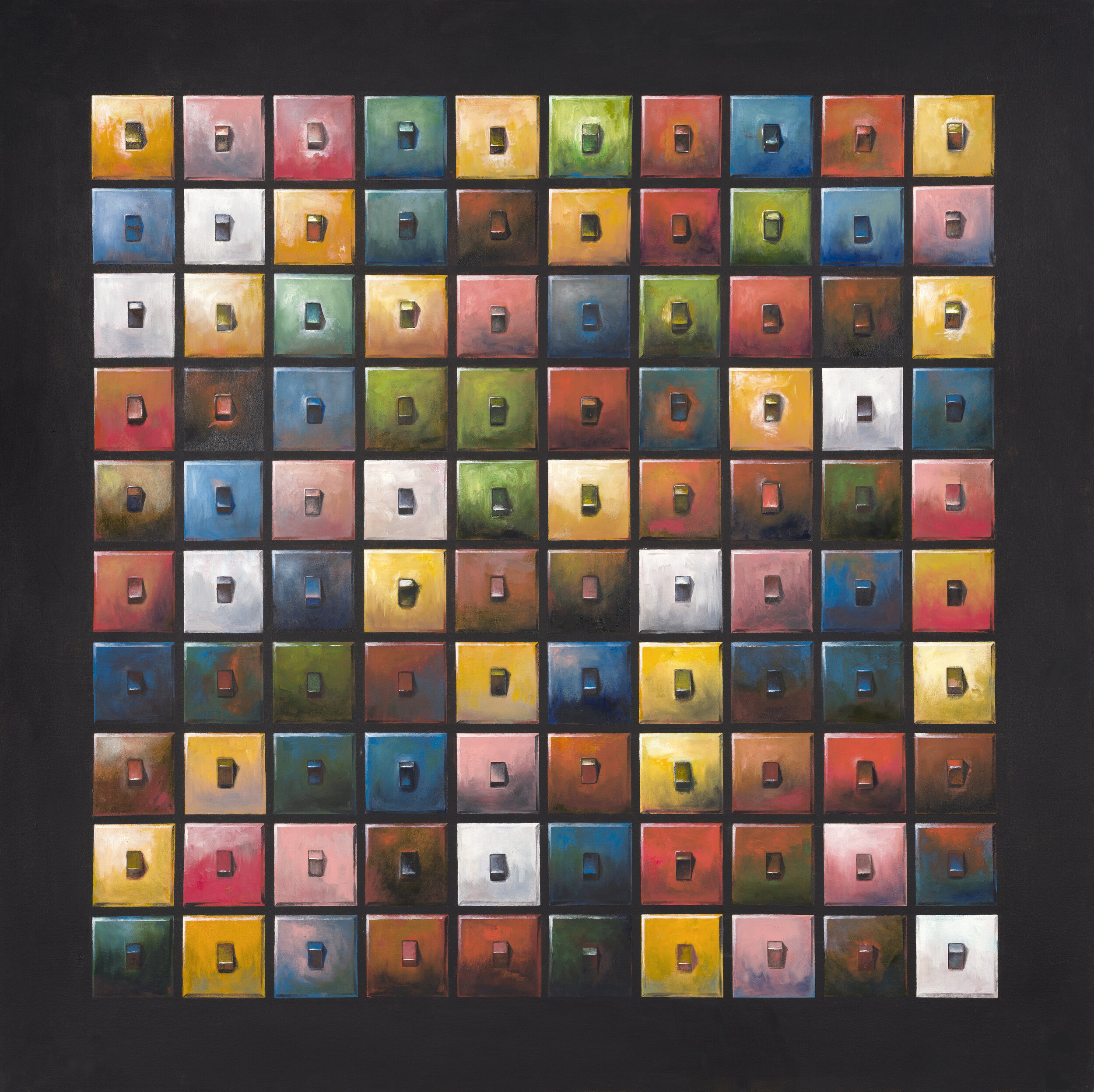

HUMBLE | Acrylic on Canvas | 120 cm * 120 cm

Despite the clean lines and the definiteness of work shown in the repetition of switches, there’s very little engineering at the point of creation. It’s a moment, where after five years of waiting, I found myself overcome by a feeling of sadness and resignation. This “moment” lasted almost 24 hours (which is how long it took the work to be completed). And ironically, it was in the acceptance of (relative) powerlessness in which I found a greater power.

A greater creative power but also a Greater Creative Power.

Qadar - Arabic for predestination – is a big thing among all humans whether they believe in a Deity or not. An atheist will question the Divine. He will ask how a cancer is allowed to occur when its position in time is already known. The early Philosophers wrestled with a Divine Will as they struggled with the nature of a Creator. On a big (political) scale, when the Omayyad Arabs of 6th Century BCE took over the Roman state of Egypt, they came into contact with Hellenist-Christian philosophy. They absorbed its techniques and methods and used it to debate whether the naughtiness the new Muslim rulers were about to practice (on rebellious elements) to sustain their existence was justifiable – freewill or otherwise. A God that knew of everything, and had powers greater than His creation…well, don’t look at me. Blame Him.

But on a smaller, every day, level a Muslim’s conversation will be peppered with “inshAllah” - If God wills. It’s so commonly said that I actually think you can forget to feel what it means. I use the word “feel” deliberately because my interest in Qadar started off as a rational thing. I was reading a line or two attributed to a man of immense wisdom, leadership and historical value: Mr Ali Abu-Talib (ra).

He was once asked: “How have you recognized your God?” And he replied: “…when I determined and was prevented from achieving my determination, and when I intended and fate contradicted my intention, I realized that the Administrator was other then me.”

I questioned as to whether I was aware, in my bones, of this. It was on my tongue, sure, but did I feel it?

I was in a hardware store surrounded by plugs and bulbs and switches and the quirky element quickly connected. Two attempts were made but I failed. There was some thought put into the motifs. Each bulb or switch would possess a dual nature: 1) a visible Front End – the painted Yes-No moment in one’s life and 2) the invisible Back End - an aspect of God represented through His unpainted, attributive name. Therefore, there’d be 99 or 100 or 102 switches. 100 could be divided into a 10*10 configuration and this would allow for the harmonious geometrical design that characterises this kind of art. Each name would be unravelled into its Arabic triliteral root. Each root would be expounded upon and linked to a front-end event when a Divine Will would have overridden or guided a lesser will. And because each switch/event was chronologically arranged, you’d have - like 100 pixels brought together to make a single face – you’d have the "face" of a human's lifetime.

The first switch was, serendipitously, the first name of God mentioned in Islam – Al-Rahman. Its Arabic roots are: Ra, Ha, Ma. It means womb which is a thing of immeasurable love, nourishment and giving. Here, I reasoned, was where the Divine Will would have first made its contribution - the womb - from choosing which two people came together, to the night of their intimacy to the egg that was released and the one sperm that fused. It determined, every day, whether the womb was strong enough to bear a child; it Willed which soul was to be poured into the growing vessel. It signed off the date of birth.

There were two attempts. Both failed. There was the sense of intellectual pretentiousness and fakery – a Velcro beard. The painting was about humility which I hadn’t sufficiently felt. I was flying high. And how do you tell a bird that its wings are neither the source of its flight nor of its identity as a bird?

It took me five years to understand. My creative reservoir dried out. This feeling of being empty, standing in front of a canvas, day after day, not being able to do anything – I eventually started asking other creatives whether such lengthy creative blocks were normal. Months turned to years. I questioned, as any spiritual person would, whether I had done something naughty but couldn’t see the God-sized finger wagging at me. I wondered whether art had been a coping mechanism for something – literally, art therapy. Now that there were no stressors, because I was flying high, I had no need for art.

“Dear so and so,” I emailed to the art studio owner, “it’s with great sadness that I’ll have to return your keys. I’m finding that [I inserted a mild excuse].”

I had decided to give back my studio, throw out the junk and bring home the rest. I spent the night emptying out the room. In the morning, there remained a single canvas and the last box of paint and brushes. The keys were in my hand, the door was open and my last action, I determined, would be to pick up the remainder and lock the door. Corner to corner, I gave the room a parting look and tried to swallow five years worth of failure. I was overcome by immense sadness, then resignation. A pause.

I locked the door and walked over to the canvas. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do but this act would have been an admission, an apology and a prayer. I picked up the brush. In a few strokes I realized that I was painting switches. One switch after another, I painted. One turned to ten, then fifty, then seventy, then a hundred. I admitted that I was neither the bird, neither the source of my flight, nor the owner of my wings. My will had been guided by a Greater Will. I was not the source of my art. Nor could I call myself a painter. Nor was I the owner of my brushes.

UM.