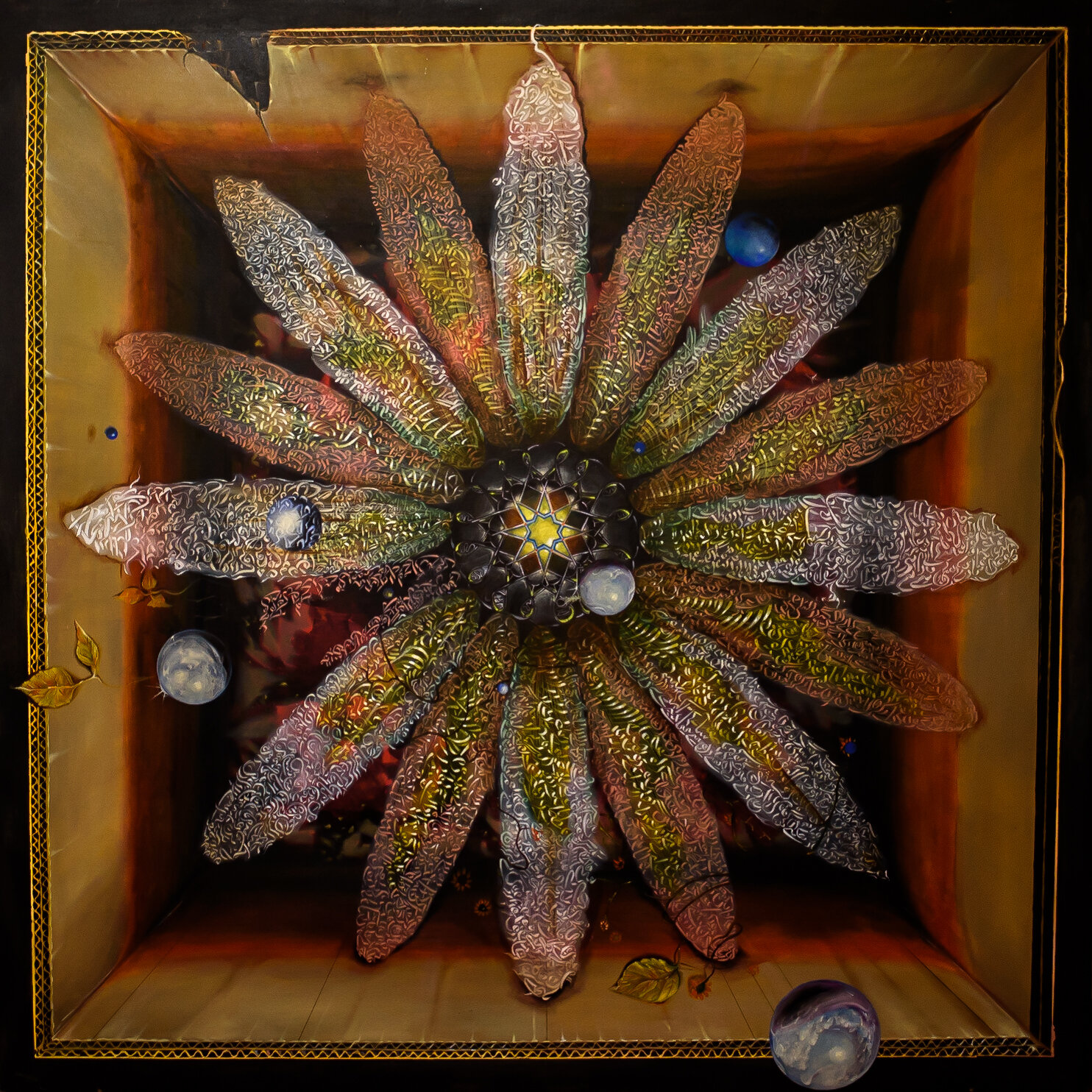

SHIKWA - THE LAMENT | Acrylic on Canvas | 150 cm * 150 cm

In August 1914, Britain entered into the 1st World War and declared war on Germany. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs from within Britain’s richest colony, India, volunteered to fight with the Allies. Other Indians had their own battles to fight.

Three years before, a young Hindustani, by now a barrister and a Professor of Philosophy - though not yet a British Knight - had stood in front of a college audience. He recited a poem – a bold, audacious work penned by himself. It was a letter of complaint – to no less, to no other, than God. The complainer was himself. Or perhaps it was a Muslim. Or perhaps it was the voice of the Indian Muslim. Or maybe it had been the entire Ummat. Whoever the protagonist, the lament came from deep within. It shook at the etiquettes of dialogue which should have existed between the created and The Creator.

The writer, Muhammed Iqbal, was born in 1877 – 20 years after the British East India Company had formerly ended the Mughal dynasty. Iqbal had previously been an Indian nationalist. He believed in the Hindu-Muslim utopia of ousting the greedy Company and reliving the good days. But this was the first decade of the 1900s and something had changed.

The 30-something-year-old Iqbal had spent time in Europe. First attaining a PhD (Munich) and then completing his Bar-at-Law in Lincoln’s Inn, he no longer felt Indian. Impressed by Western education, Iqbal had become exposed to the philosophy of Kant, Nietzche, Goethe and Aquinas. They inspired his Islamic religion and, “The Western Storm” he later wrote, “had turned the Muslim into the real Muslim.” The same Europe, its nationalism this time, had made him part from his own Indian nationalism. Europe’s downfall, Iqbal prophesised, would be her borders. Several years later, European countries went to war.

No! Iqbal would no longer be an ethnic Indian of India but a Muslim of the world.

I had felt immense hurt within the poem. Though wild in its energy, and Iqbal’s Sufi heritage allowed for the protagonist to address his Beloved intimately, the accusations came across childlike in their innocence. It made The Lament more of a cry – a cry for help.

“Nevertheless, there is this complain to us that we are not faithful,

If we are not faithful, then You too are not generous.”

It’s important to ask why Iqbal’s pathetic protagonist displays jealousy towards others, cries poverty and accuses God of abandoning him. This, after all the things he has built, destroyed and sacrificed for his worship alone.

Iqbal’s Islamic world had been in decay. The Mughals did not implement Islamic law onto heterogeneous India but they were nevertheless Muslims. Their end in 1858 at the hands of the British led to the Indian Muslims’ humiliation. They were educationally held back, economically backwards and trailing behind the modernising Hindu Indian. 1911, France took Morocco and Italy had occupied Libya. By the late 1800s, Russia’s conquest of Turkestan was complete. The Ottoman Empire was the sick man of Europe. A few years after the 1st World War it would be dismantled. In 1903 the Sokoto Caliphate of West Africa would also be defeated by the British. The Qajar dynasty of Iran had lost territory to the British and become indebted to Russia.

In 1865, James Maxwell proposed that light was an electromagnetic wave. In 1859, Darwin had published his book, On the Origin of Species. In 1880, Pasteur convinced everyone of the germ theory. In 1843, Alexander Bain invented the fax machine and about the same time the telephone was invented too. In 1903, two Americans had flown the first ever heavier-than-air aircraft. In 1899, Sigmund Freud had published his book, The Interpretation of Dreams. In 1859 the philosopher and economist, John Stewart Mill, had published: On Liberty. There was David Ricardo’s 1817, The Principles of economy and taxation. Karl Marx published the Communist Manifesto in 1848 and Das Kapital in 1867. In 1905, Einstein had written a paper on special theory of relativity. Charles Babbage had invented the first computer in 1835. 1862, Alexander Parkes invented plastic.

Andalucia, Baghdad and Samarkand had once been the realms of knowledge. In 1870, the second Industrial Revolution swept through Europe, America and Japan, bringing with it incredible wealth. Metallurgy & mechanisation, electrification, chemical engineering, rails and automobiles, photography and even the pigments for visual art and the colour purple, there was nothing here that Iqbal’s protagonist could lay claim to. Not even the electric light bulb – that was Humphry Davy in 1809.

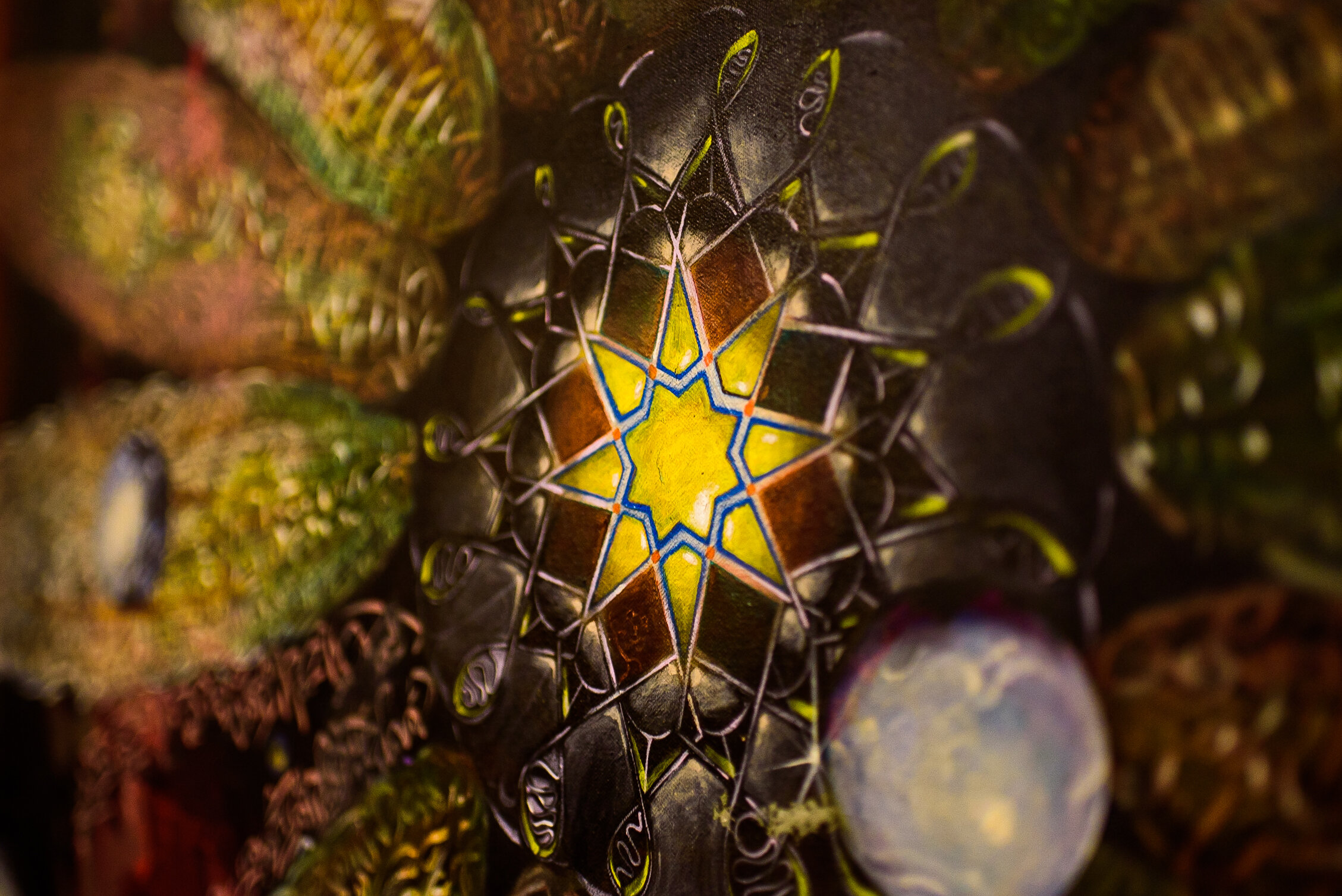

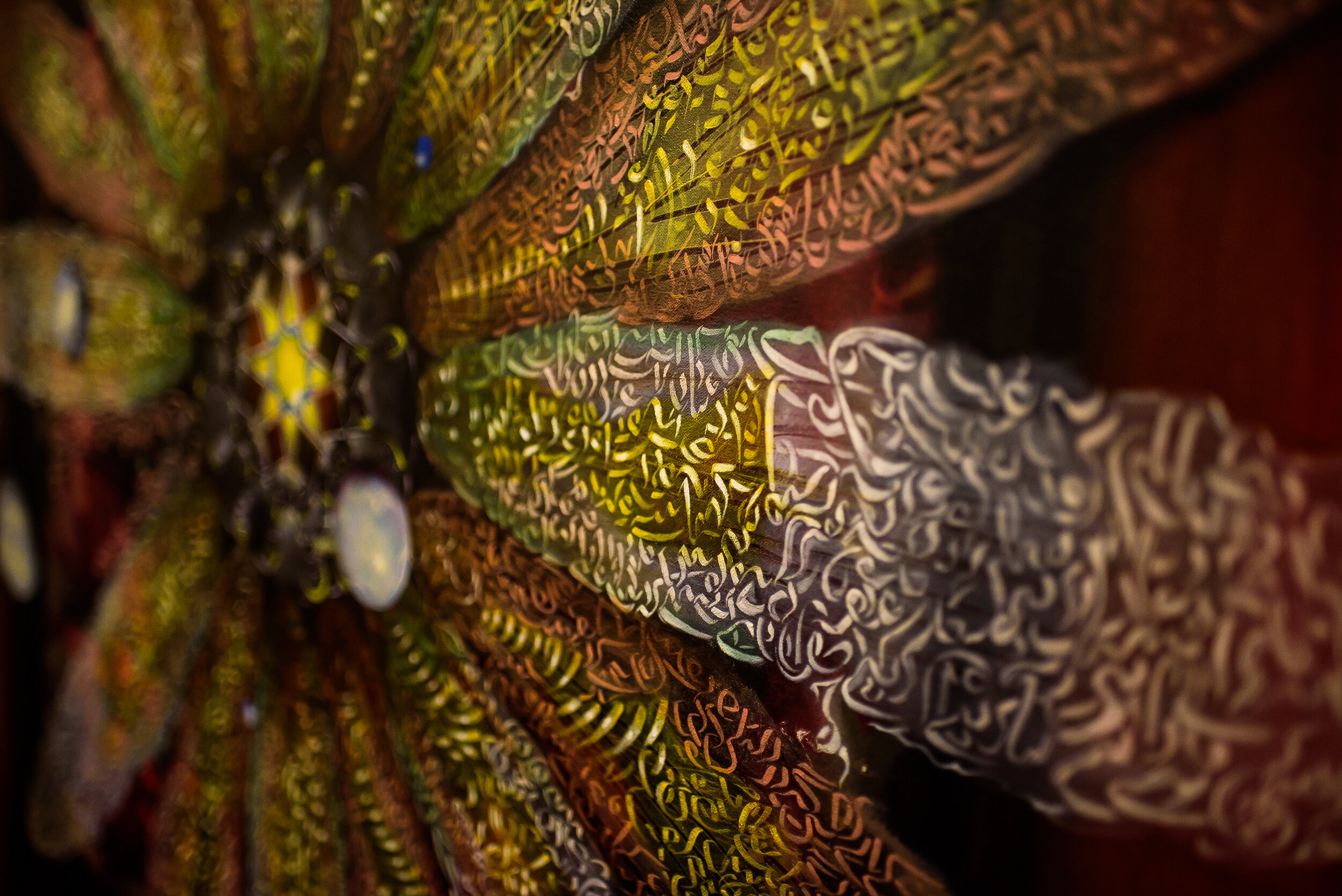

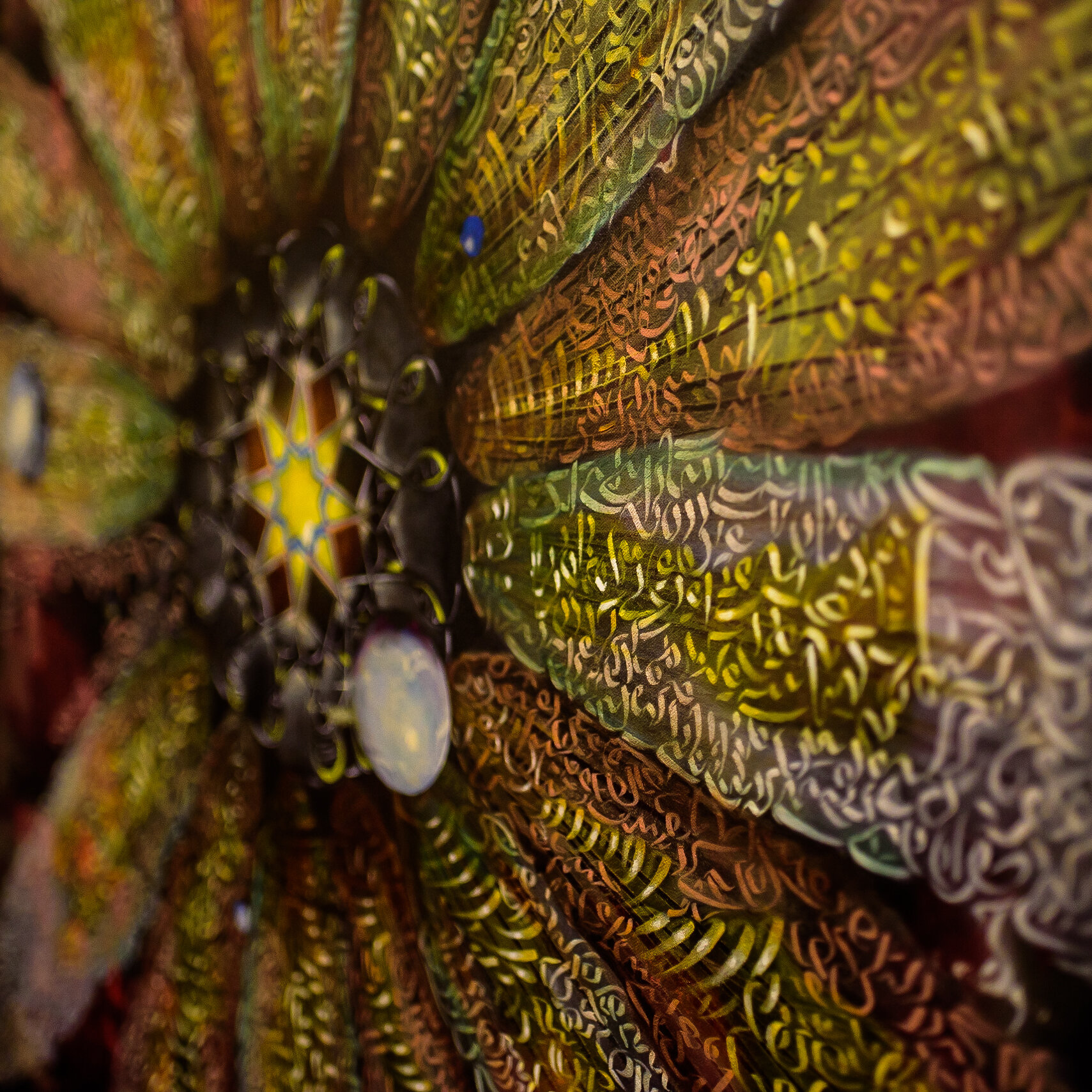

My place in this Urdu poem, save that of a reader, is nil. Even within the painting, I’ve merely given the 186 lines of poetry a new analogy. I’ve read into the black ink and been moved sufficiently by it for his words (in my mind) to attain energy and evaporate into a temporary cloud of semi-incoherent meanings. Through focus/unfocus I've tried to discover a new coherent pattern inside the cloud of a million associations. I’ve then collapsed the cloud into a new and single strongmeaning – a dying flower staring heavenwards for the rain. Each petal, save one, comprises of a pair of six-line stanzas. The words deliberately lack the Urdu vowel marks. This error action is borrowed from the traditional Islamic artists. It is intended to convey respect to the poet, as if to say, I will not be able to add to your work.

UM.